In an ever-changing world, stress invades our lives to varying degrees. For healthcare professionals like massage therapists, understanding the underlying mechanisms of stress is essential. Indeed, beyond massage techniques, their role often involves helping people to manage this ubiquitous phenomenon. In this article, we explore stress as a natural coping mechanism, its impact on the body, and why it’s crucial to know how it works in order to manage it better.

| Contents: What is stress? Stress: a three-phase response An adaptive… but sometimes harmful mechanism How does massage relate to stress? Relearning how to manage stress |

What is stress?

Stress is the body’s physiological and psychological response to a situation perceived as threatening or demanding. This mechanism is essential to survival: it mobilizes the energy needed to escape danger or solve a problem. Without stress, we wouldn’t get up in the morning, we wouldn’t react to dangers, and our adaptation to change would be severely limited.

However, when stress becomes too intense or persists over a long period, it can have deleterious effects on both body and mind. These states of “over-stress” are often associated with disorders such as anxiety attacks or burn-out. So, understanding the mechanisms of stress is the first step towards better management, notably through therapeutic approaches such as massage.

Stress: a three-phase response

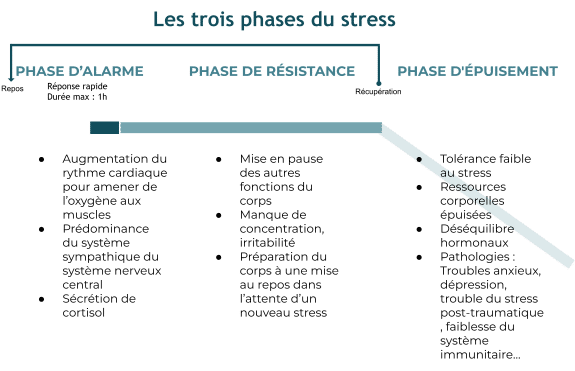

Physiologist Hans Selye described the General Adaptation Syndrome (GAS ) to explain the body’s response to stress, in three phases:

- The alarm phase: Faced with a stressor, the body mobilizes its resources to respond rapidly. This activation takes place via the hypothalamus, which releases a hormone called CRH (corticotropin-releasing hormone). This stimulates the pituitary to produce ACTH, triggering a hormonal cascade. Within seconds, the adrenal glands release cortisol, accelerating heart rate, mobilizing muscle energy and increasing alertness.

- The resistance phase: If the stressor persists, the body adapts by maintaining a high level of vigilance, but at the cost of a sustained mobilization of its resources. At this stage, the digestive, immune and reproductive systems are often put on standby to prioritize the emergency.

- The exhaustion phase: When stress becomes chronic, reserves are depleted, and coping mechanisms show their limits. Contrary to Selye’s initial view, this phase is not simply “general fatigue”, but rather a complex dysfunction marked by hormonal imbalances, notably hypersecretion of glucocorticoids such as cortisol.

An adaptive mechanism… but sometimes harmful

Under normal conditions, stress plays a beneficial role: it improves cognitive performance, stimulates learning and mobilizes the body in the face of challenges. What some call “eustress” (good stress) is a form of positive energy that drives us to action. However, when it persists or becomes excessive, it can lead to major imbalances.

Cortisol, a key stress response hormone, can, in the event of prolonged hypersecretion, disrupt memory, inhibit repair functions (wound healing, cell regeneration), and even cause neuronal death in areas such as the hippocampus. These effects explain why chronic stress is often associated with somatic and psychic disorders, ranging from digestive problems to depression.

Stress also affects our biological rhythms. Ultradian cycles (90 minutes) punctuate our days, alternating between periods of activity and rest. Under chronic stress, these cycles can become desynchronized, disrupting sleep, digestion and sex life.

What’s the link with massage?

For massage professionals, stress is a central issue. Many people consult us to relieve physical tension or pain, which are often somatic expressions of stress.

Understanding the physiological mechanisms of stress enables us to adapt massage techniques to act in a more targeted way. For example:

- Relaxing massages (such as Swedish or Californian) help reduce cortisol levels.

- Breathing techniques integrated into the treatment can stimulate cardiac coherence, a practice recognized for regulating stress response.

- Finally, creating a space of disconnection during the session helps the nervous system to switch from a state of alert (sympathetic system) to a state of rest and regeneration (parasympathetic system).

Relearning how to manage stress

Fortunately, it is possible to improve our ability to manage stress. A healthy lifestyle plays a key role:

- Physical activity: sport helps release accumulated tension.

- Breathing techniques: cardiac coherence, meditation or yoga to calm the nervous system.

- Sufficient rest: respect biological rhythms to promote regeneration.

- Limiting stimulants: avoid excessive coffee, alcohol or other stressful substances.

Finally, for people suffering from chronic stress (as ingeneralized anxiety disorder), manual therapies such as massage can complement a global approach, offering a moment of relaxation as well as valuable support in regulating the body.

Stress, while inevitable, is not an enemy. It’s a natural mechanism which, if properly managed, can become an ally in adapting to a world in perpetual motion. As massage professionals, understanding these subtleties is a strength in supporting people in their quest for well-being and balance.

To remember:

- Stress is a natural mechanism, essential for survival and adaptation, but it can become harmful if it persists.

- The three phases of stress: alarm (mobilization), resistance (prolonged adaptation), exhaustion (imbalances).

- Chronic stress can cause hormonal imbalances, somatic and cognitive disorders (memory, digestion, sleep).

- Relaxation techniques can provide support by reducing cortisol and helping to regulate the nervous system, enabling the system to emerge from the exhaustion phase.

Sources :

- Guillet, L. (2012). Chapter 1. Models of stress. Le stress ( p. 9 -38 ). De Boeck Supérieur. https://shs.cairn.info/le-stress–9782804174378-page-9?lang=fr.

- Juruena, M. F., Eror, F., Cleare, A. J., & Young, A. H. (2020). The Role of Early Life Stress in HPA Axis and Anxiety. Advances In Experimental Medicine And Biology, 141-153. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-32-9705-0_9.

- Stora, J. (2019). Chapter IV. Neurobiological mechanisms and diseases of stress. Le stress ( p. 85 -105 ). Presses Universitaires de France. https://stm.cairn.info/le-stress–9782715402089-page-85?lang=fr.